Google is the only major platform provider that has to fight with an ecosystem it doesn’t own. Apple can do what they want on the Apple platform, on Amazon and Facebook / Instagram it looks very similar too: closed systems with complete control.

Carrying this architectural disadvantage though, Google progresses: Google dominates the desktop browser market with Chrome and the smartphone market with Android. Smaller initiatives from Mountain View also go in this direction but luckily they are not all out there to restructure the Internet like AMP. For some time now Google has been pushing the use of SSL very strongly and pushing for mobile-first websites.

Since Google cannot simply force website operators into change, the search engine operator relies on another methods, like better Google rankings. The use of SSL has already become a ranking factor and mobile friendliness of websites has also reached this status.

In the past few weeks, Google has announced in a blog post that it will roll-up its desires for website operators in the page experience ranking factor. In addition to the well-known wishes for HTTPS use, safe browsing, mobile friendliness and the absence of annoying interstitials, three new values will be added next year: the Core Web Vitals

What are the Core Web Vitals?

With the Web Vitals, Google wants to establish a number of metrics to make the user experience of a page measurable. Google focuses here on technical performance issues. The Core Web Vitals are three elementary metrics with which Google wants to make the page / user experience comparable. These are the three measurements:

Largest Contentful Paint (LCP)

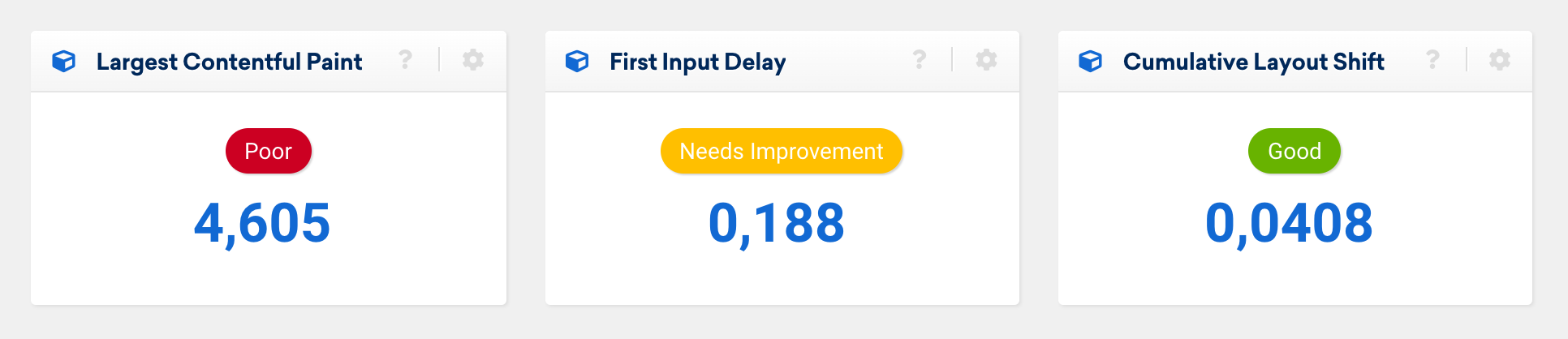

The first Core Web Vital measures how much time passes before the main content of the website is visible to the user in the browser. While in the past attention was paid to the first appearance of content (First Contentful Paint / FCP), they have moved on and now measure how long it takes for the main content to appear.

The time between the request of the page and the appearance of the main content in the browser is measured in seconds. Google gives us the following ratings for the metric:

- Good – less than 2.5 seconds

- Needs improvement – up to 4 seconds

- Poor – more than 4 seconds

First Input Delay (FID)

This is all about measuring how quickly the user can interact with the page. When a page is loaded, users usually want to interact with it: fill out a form, zoom into pictures or just click on a link – the First Input Delay measures how well this works.

Specifically, the time span between the interaction and the point in time at which the browser reacts to this interaction is measured

- Good – less than 0.1 seconds

- Needs improvement – up to 0.3 seconds

- Poor – more than 0.3 seconds

Cumulative Layout Shift (CLS)

The last of the three metrics of the Core Web Vitals deals with the visual stability of a web page. Increasingly complex web pages load parts of the content in the background (asynchronously) in order to keep loading times low for the user. If these loading processes are not coordinated, this can cause the content of the page to jump around while the user is already trying to read it.

This metric is the least intuitive: Google essentially measures how often elements that are already visible are subsequently moved and weights them by how far they are moved (more detail).

- Good – less than 0.1

- Needs improvement – up to 2.5

- Poor – more than 0.25

Google has already announced that the composition of the Core Web Vitals does not necessarily have to adhere the three metrics presented now, and expressly reserves the right to change them. Changes will , however, be announced, and there will be enough time to adjust to any new metrics.

How will the Core Web Vitals be measured?

There are two fundamentally different approaches to measuring the Google Core Web Vitals: the first is so-called laboratory data. Synthetic measurements are carried out under self-controlled circumstances (hence the name).

Laboratory data

Laboratory data (lab data) has the advantage that it is reproducible, i.e. always delivers the same result, as long as you do not make any changes to the circumstances and parameters.

Lab data is particularly suitable for debugging and for the continuous improvement of your own website. For example, we recently switched the performance measurement in the Optimizer to collecting lab data based on Google Lighthouse. Based on this, you can reliably track how changes to the website affect the values of the Core Web Vitals.

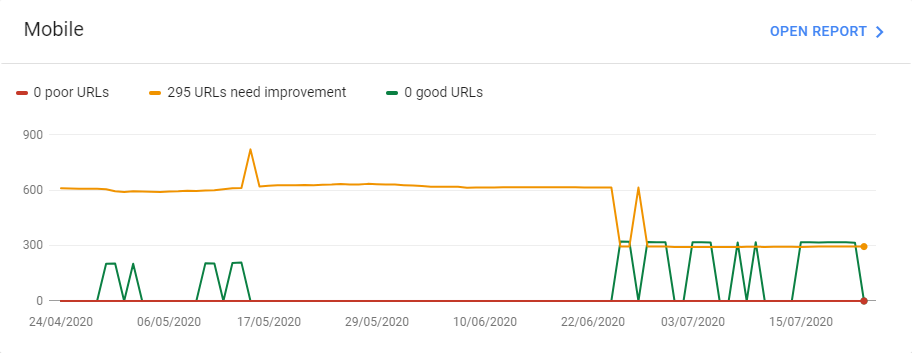

The second approach is to use so-called field data. The respective, individual values of the Core Web Vitals are measured and evaluated by real users of your website.

Field Data

This can either be done via individual JavaScript integration (Google also provides a solution for this) or via automatic measurements that Google Chrome automatically takes for some of the Chrome users. Google uses field data in the Core Web Vitals report in the Google Search Console.

The advantage of user data is that it best reflects the real user experience. However, improvements in the Core Web Vitals only show up after a delay. There are also factors that website operators have no direct influence over. Despite this, Google has announced that the Core Web Vitals ranking factor will be based on the field data.

How can I improve the Core Web Vitals?

While the discussion until now was relatively simple, we now come to the unpleasant part: the actual work. The bad news right at the beginning. There is no easy solution to improving the Core Web Vitals.

Every page and every system is different and has to be optimised differently. The Core Web Vitals are (besides JavaScript crawling) probably the most technically demanding part of search engine optimisation at the moment, because you have to understand many Internet technologies in order to be able to understand them.

Google has extensive documentation about the Core Web Vitals online and also points out typical improvement options for each metric. Typical key factors are:

- LCP: Server response time, render-blocking CSS and Javascript, loading time for resources (images, CSS) and client side rendering. (more)

- FID: Reduce the impact of third-party code, speed up JavaScript execution, minimise the main thread load, reduce the number of requests and keep transfer sizes small. (more)

- CLS: Sizing of images and video elements, do not automatically insert content above existing conten, use animations that do not trigger layout changes. (more)

In practice, the improvement of Core Web Vitals follows a process of regularly checking the metrics for your website based on laboratory data, and then checking at longer intervals to see whether the (theoretical) improvements also apply to users (field data).

Core Web Vitals from 2021 as a ranking factor

Google has announced that the Core Web Vitals will not become a ranking factor before next year. They have also committed to an additional notification six months before the specific date on which it will happen.

The switch to the Mobile First Index was only postponed recently from September 2020 to March 2021. Therefore it’s likely that the Core Web Vitals will be made a ranking factor in the second half of 2021.

Nevertheless, it is not advisable to postpone the task for too long. On the one hand, Google is driving improvements that will also help you outside of pure SEO: faster, user-friendly websites not only make Googlebot happy, but your real users too.

On the other hand, improvements to the Core Web Vitals are technically complex and are likely to take time. In addition, more time will pass before the effects of these improvements are seen in the field data. We say: better to start planning and acting now than in 6 months.