So far, much of this strategy guide has been about “doing the groundwork”: researching keywords, planning website structure and also thinking about the presentation in the search results. All of this is certainly important, but still: content is king. So, what should the content on a page ideally look like?

- Content = Text

- Quality as the Highest Principle

- Overview of Important Content Principles

- Principle #1: Content must answer the question

- Principle #2: Content must cover the topic completely

- Principle #3: High level of care

- Principle #4: One-sided or two-sided?

- Principle #5: Structure and readability

- Principle #6: Linking to relevant sources

- Principle #7: Own content

- WDF*IDF or not?

- The SISTRIX Content Assistant

- Featured Snippets

- Text, text, text – but what else belongs on a page?

- Main Heading

- Subheadings

- URL/Path

- Images, Media

- Conclusion

- The SEO Strategy Guide

- SEO Strategy Made Easy

- Competitor Analysis Made Easy

- Keyword Research Made Easy

- Determine Search Intent and Plan Website Structure

- Optimise Search Results and Generate More Clicks

- Create and Optimise Content

- Internal Linking

- International SEO

- Link Building Strategy

- Use Google Search Console + Google Verticals

Content = Text

Foremost, content primarily involves text. Although Google has recently improved its ability to recognise audio and video content and can, for example, extract relevant topics directly from podcast episodes, text is still considered most relevant for “normal” Google searches.

Here, one important principle applies: quality beats quantity. Generally, it is never a matter of reaching a certain word count. More words are also not necessarily better than a few. As John Mueller from Google noted in a tweet, Pinterest ranks for a lot of search queries – and certainly not because of the enormous amounts of text that exist there.

Factors such as keyword density, which used to be common, are also a thing of the past. Certainly, whether a search query appears reasonably often on a page or not at all may still have some influence. But the rigorous rules that were used in the past really don’t lend themselves any more.

Quality as the Highest Principle

If quality is really that important, the crucial question naturally arises: What makes up a high-quality text?

Unfortunately, Google provides no specific guidelines on this – which would also not be possible considering the complexity of the topic. Google does not say that a page needs to have at least 350 words and that there should be at least two images, or that a paragraph should always be about 50 words long.

Instead, Google helps us with two documents regarding the topic of quality: the Quality Rater Guidelines and the Panda questions. But again, what is found in the documents does not provide clear guidance, but is more in oracle form – or, as with the Panda questions, in the form of questions with which you can critically question your own content.

The Quality Rater Guidelines in particular – a document designed to guide Google’s employed search results testers – have become increasingly important in recent years, especially because Google likes to use this document as a reference in its external communication. Of course, it is advisable for anyone who wants to conduct serious SEO to go through this document in its entirety at least once. But even after doing so, you will not necessarily be smarter, as these are not clear rules but rather examples and principles.

Overview of Important Content Principles

As stated before, those who want to get to know all of Google’s requirements as concretely as possible, should at least read the Quality Rater Guidelines. The following, however, is a summary of the most important principles from the Guidelines and the Panda questions.

One more important thing: Google already has high demands, that are raised even higher for the so-called YMYL (Your Money or Your Life) area. These are mainly topics from the fields of medicine, finance and legal advice – in other words, topics where it is a matter of (somewhat dramatically formulated) “money or life”.

The topic of E-A-T also plays a role: Here, Expertise, Authoritativeness and Trustworthiness are significant. The website as well as the author (“creator”) should have expertise and should be authoritative and trustworthy – this especially for YMYL topics. E-A-T is not about requirements that can be met by writing only a single article. Whether one is a recognised expert or not will be determined by Google based on many factors, especially external ones.

Principle #1: Content must answer the question

This principle is quite simple. If someone searches for “hearing aid costs”, they want to know how much hearing aids cost. It used to be easy to rank for such a search term simply by including phrases such as “If you want to know how much hearing aids cost, just come to our store” on a page. The keywords appeared in the content, but the user’s intent was definitively not fulfilled.

That is why it is important that the content fulfils the need for information behind the search query. In this case: a price or at least a price range should be mentioned concretely in order to satisfy the user intent.

Principle #2: Content must cover the topic completely

The content should also explore the topic in depth. Anyone writing content on the cost of hearing aids can, of course, simply mention a few numbers as a cost framework. However, this does not go into depth. Potential buyers of hearing aids may ask themselves many questions:

- What financial aid does health insurance offer?

- What about private health insurance?

- What are the minimum requirements a hearing aid must meet? What features are available in higher price ranges?

- Is it possible to deduct the expenses from the tax?

- How often is one entitled to a new hearing aid?

- …

The article should cover all these topics in order to fully explore the subject. Even if the search query “hearing aid costs” doesn’t lead you to expect it, the average user has many questions that they don’t explicitly type into the search field at that moment. The article should still be able to answer these implicit questions.

Principle #3: High level of care

Within the framework of the Panda questions, Google suggests that an article should be designed in such a way that it could appear in a book, a newspaper or an encyclopedia. Content that meets these requirements will approach the topic in a rather non-promotional way and will focus on a neutral solution to the problem.

There are also various references to topics such as grammar or spelling – aspects that can also be summarised under “final check”. It is still doubtful whether Google is able to recognise incorrect facts in a document. Incorrect punctuation or spelling mistakes, however, are probably much easier to recognise.

Principle #4: One-sided or two-sided?

There are also clear indications that articles should examine a topic from multiple perspectives (e.g., pros and cons) – ideally from all available sides. If, for example, a medical topic only deals with a certain alternative medical treatment of the disease X, it is virtually impossible for the article to also be found for the search query X.

Overall, it seems that alternative perspectives have difficulties permeating the search results and that the search results tend to develop in the direction of the majority opinion/mainstream.

Principle #5: Structure and readability

If an article should be so good that it could also be printed (see Principle #3), then it must also be well-structured. This calls for meaningful subheadings but also other types of formatting: sorted and unsorted lists, tables, bold fonts for important aspects, and so on.

This is especially helpful for users who are nowadays often divided into scanners and skimmers, i.e., those who are not willing to read an article from the first to the last word. Rather, most users will seek visual aid in order to efficiently read only relevant parts of the text. An article needs to offer this aid so that the user does not immediately leave the website in the hope of finding a more quickly understandable article elsewhere.

Principle #6: Linking to relevant sources

Some website owners are “afraid” of linking to other sources, based on various myths that doing so drains PageRank, for example. But following the analogy to books or encyclopedias: there, it is normal to link relevant sources as well.

This is relatively easy with medical topics, where you can always link to a study, a Wikipedia page or an expert. In an article about the correct laying of parquet, this becomes more difficult. So, if it makes sense to link relevant sources, you should also do so – but not necessarily by rule (i.e., “We must always link at least two websites”).

Principle #7: Own content

It goes without saying: if you create content that strongly resembles other sources, you have relatively low chances of ranking.

The implementation of this principle depends strongly on the subject area. Especially when it comes to medical topics, it is not always possible and in some cases not even desirable to reinvent the wheel. Aspects like “diagnosis” or “therapy” necessarily belong in an article about a specific indication. What is important in any case, however, is not to simply copy other content or to lean very heavily on it. Content should be independent and have a clear added value to other established content on the same topic.

WDF*IDF or not?

One question arises in addition to all the principles: Many SEOs use WDF*IDF tools to valorise content for search engines. What is this all about?

Search engines have billions of webpages in their index – certainly millions of pages for some search terms like “aspirin”. If Google were to put these aspirin pages next to each other and compare them, you would notice that there are certain words that occur very frequently – and that also do not appear on pages where “aspirin” does not occur. Words such as “bayer”, “headache” or “acetylsalicylic acid” occur there with a certain frequency/probability. Now, if someone who has no idea about the subject were to write an article, they would seldom incorporate these words, while an aspirin professional would include these words automatically. Therefore, search engines can easily assess a text based on this distribution and rate them poorly if the typical “accompanying words” are missing.

WDF*IDF is a formula that calculates which words often occur in combination with a specific word (or combination of words). Many SEOs then use appropriate tools to adjust the text according to these words.

Sounds good – but this raises two questions:

- Does Google use WDF*IDF the same way? In view of the multitude of algorithms Google uses to assess text, it is safe to assume that it is much more complex in reality.

- Can the common WDF*IDF tools determine correct data? Google can access its entire index (millions of pages), while most tools only look at a handful of pages to determine the data. Therefore, the data is definitely not as reliable, as one might think.

This does not mean that using WDF*IDF is worthless. You just have to be very critical with the data. Just because the tool thinks that the word “cuxhaven” should appear in the text five times after doing keyword research for “holiday home”, does not mean that you should also do so – especially if you do not have a holiday home in Cuxhaven yourself. Again, the common tools have a database that is not sufficient to provide error-free recommendations.

The SISTRIX Content Assistant

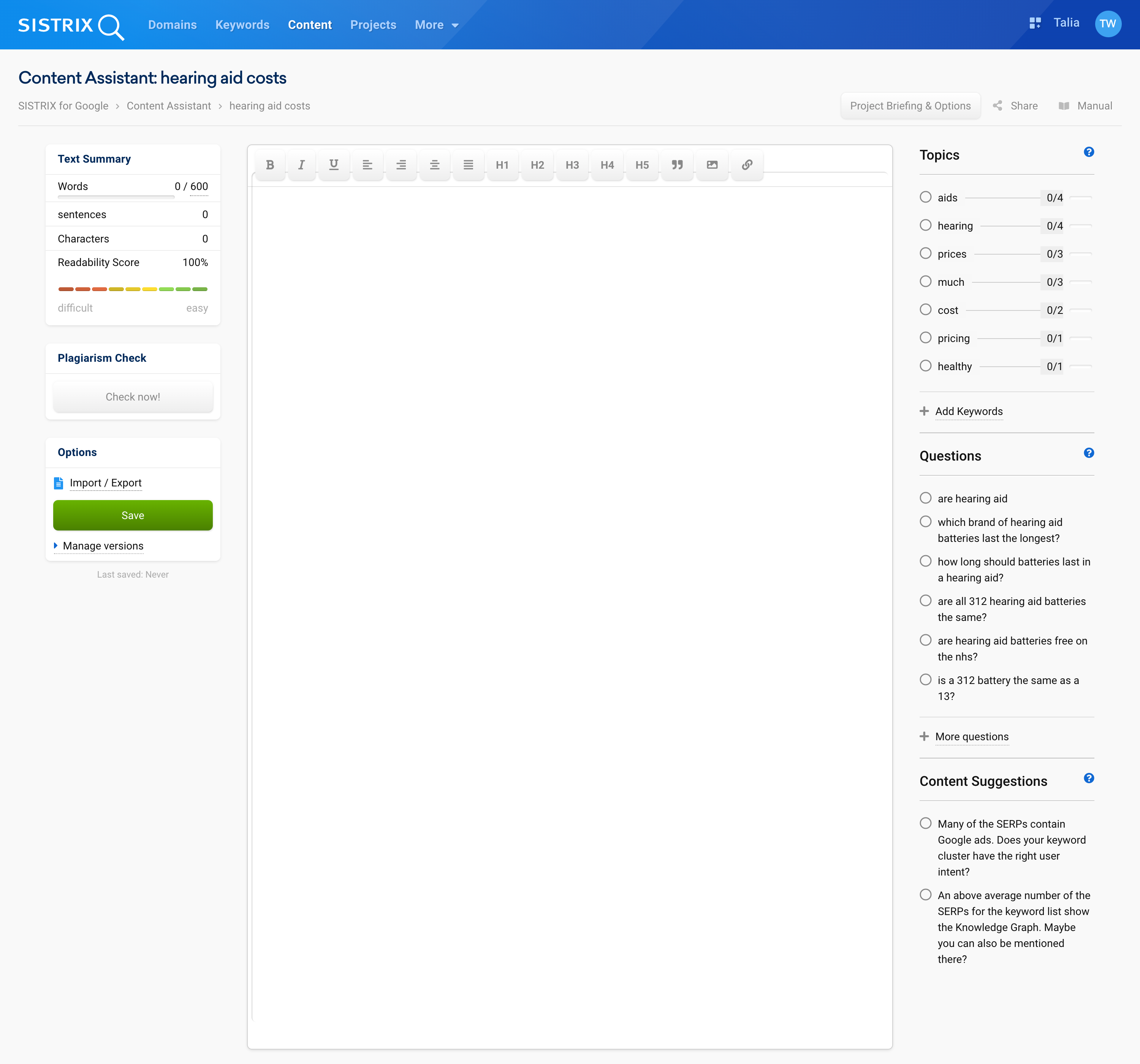

The Content Assistant (in the Optimizer module) can help with the optimal creation and the subsequent optimisation of content:

The Content Assistant has a visual editor in the middle area where texts can be written. The Text Summary (in the top left) displays simple data on text volume and readability.

The area on the right is even more exciting, because specific recommendations regarding the scope of the text are made here. Under “Topics” you can find concrete aspects/words that can be incorporated into the text. “Questions” is certainly the most helpful tool to get content support: What questions do people ask about the topic that should also be answered in the text?

Specific recommendations for certain optimisation strategies, such as targeting Featured Snippets (see below), can be found in the “Content Suggestions” section.

Here, it is important not to slavishly follow such recommendations. Everything output by the Content Assistant and many other tools is not based on human analysis, but only on algorithms. So, for example, if the question “How much does a hearing aid from Audibene cost?” is suggested, this does not necessarily mean that this question must also be answered in the content.

Featured Snippets

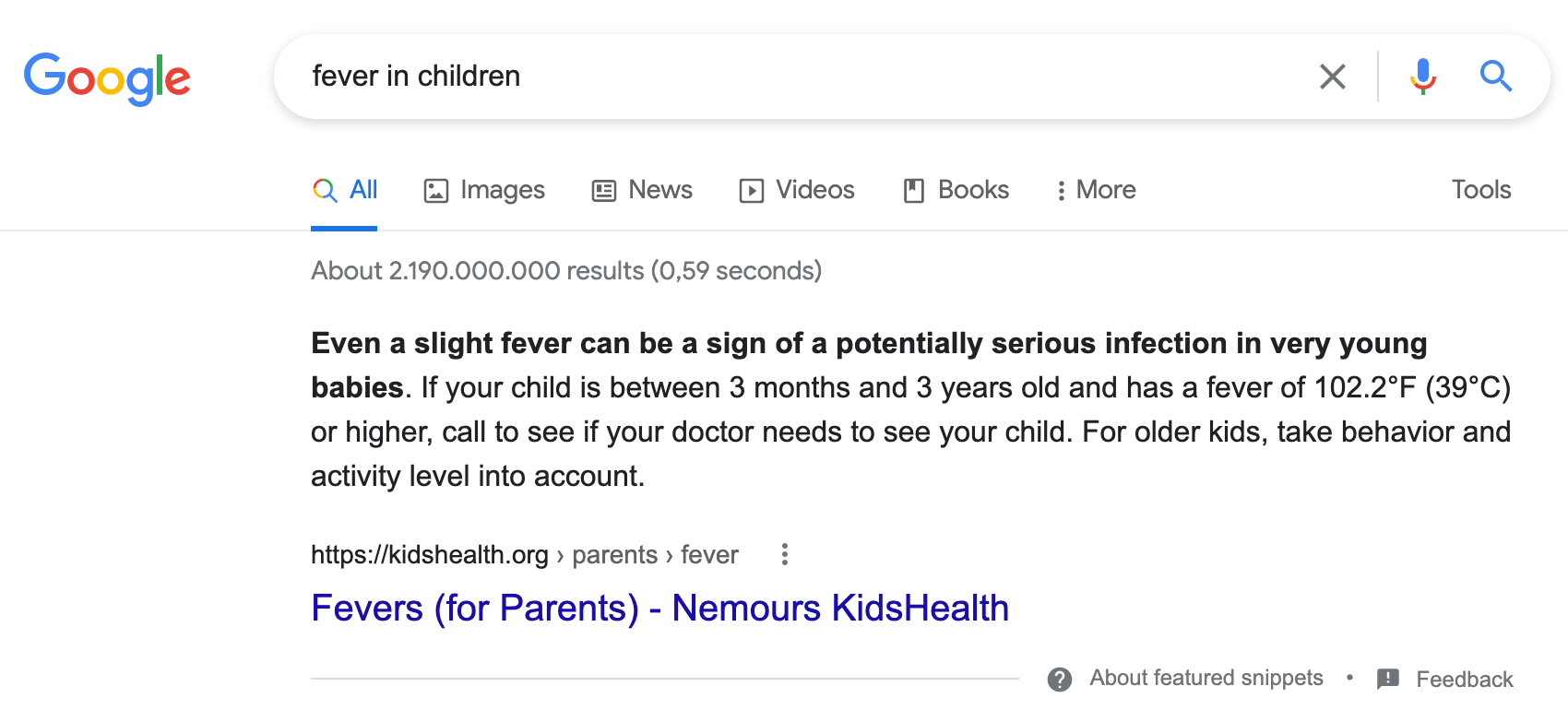

A topic that needs to be addressed in the content of text is Featured Snippets. This is a highlighted text excerpt – as shown here, for a medical search query:

The advantage of Featured Snippets is evident: you get a prominent display that can potentially lead to more clicks. Unfortunately, there are also disadvantages: Since the Featured Snippet often already provides the complete answer – as in this case – there is no reason to click through to the website any more. A Featured Snippet can lead to fewer clicks here.

On average, however, observations show that Featured Snippets are still to be viewed positively. Whoever wants to profit from that needs to ensure that their texts contain relatively short sections that compactly answer a specific question.

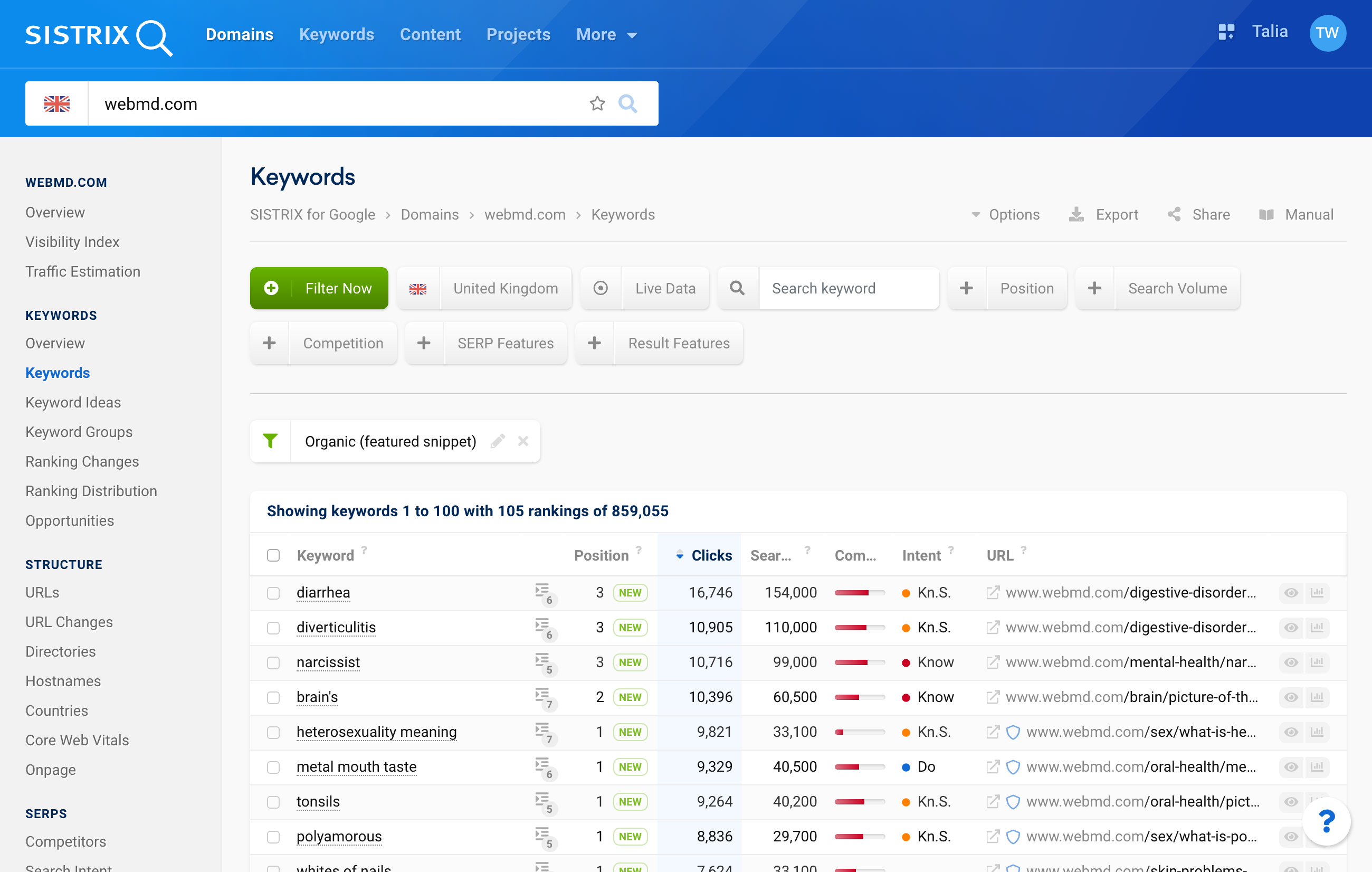

So, for example, if you want to “steal” other websites’ Featured Snippets, you can simply check in SISTRIX for which search queries Featured Snippets already exist – and then optimise your own texts accordingly.

Text, text, text – but what else belongs on a page?

So far, this guide has only dealt with the topic of text. However, a page has other components that should not be forgotten.

Main Heading

The main heading is usually what the user notices first when visiting a particular page. Therefore, it should be related to the search terms that are involved – and also emphasise the relevance of the content. A main heading like “Investing Money for Kids” is rather boring, while “Investing Money for Kids: Three Simple and Safe Investment Strategies for Parents” is more likely to engage visitors with the content.

Of course, it is important that the expectations that are created correspond to the actual service. For example, there are quite a few headings such as “10 Simple Ways to Become a Millionaire in 2 Years” that usually bring a lot of clicks, but do not necessarily meet user expectations.

Subheadings

As stated above, subheadings are especially important, as they help structure the content. Naturally, these are also another good opportunity to incorporate search terms.

In any case, it is important that the subheadings help indicate what the text below them is about. Subheadings like “Advantages of X” and “Disadvantages of X” are comprehensible, so that someone who is only interested in the advantages can skip over the text about the disadvantages. However, someone who relies on subheadings such as “Thus Spoke Zarathustra” or “Cogito ergo sum” will potentially only annoy their visitors.

URL/Path

Depending on the CMS, the URL path is generated based on the main heading. However, it is often possible to change this URL slug afterwards. Even if the influence of the URL path is very low, you should still use this opportunity and remove all filler words. If a page is targeted at the search term “investing money for kids” then the URL path could be /blog/investing-money-for-kids and not /blog/investing-money-for-kids-three-simple-and-safe-investment-strategies-for-parents.

Images, Media

A question that is often asked: Do I need to incorporate images into my article? And videos? There is no general answer to this question, of course. John Mueller from Google once put it this way:

“A YouTube video alone doesn’t make a page high-quality :), but you can certainly use videos as a way of providing more information to users.”

Therefore, there is no clear requirement that pictures and videos should be included in an article. However, you can use Google search (or SISTRIX) to find out if it makes sense to do so. For example, if you run a search query like “hairstyle trends”, you will immediately find the Google image search with a lot of images displayed in the first place in the search results. This is a clear indication that this is a visual topic and that an article without any images will certainly not be interesting for users.

If you include images in your article, you should make sure to also optimise these images. This includes at least the following measures:

- Speaking image URL (/hairstyle-trend-blue-hair.jpg instead of /dscn8828.jpg)

- An alt attribute that describes the image

- A caption

Conclusion

There is no general answer to the question of what content should look like. Fortunately, however, Google has provided many cornerstones.

Above all, content creation is all about quality and depth of content. The analogy with a book page is not so bad at all: You put effort into an article. There is a clear structure. An editor does a final check of the content. And you can proudly put your name under your work.

The SEO Strategy Guide

Take the next step in this training program. This set of learning documents will help improve your SEO results and the way you use SISTRIX.

Overview

SEO Strategy Made Easy

Introduction to the SISTRIX step-by-step guide

Create and Optimise Content

Which factors constitute truly good content?

This guide was created in cooperation with Markus Hövener from Bloofusion. Your feedback is welcome.